God So Loved The World - A Passiontide Sequence

The Chapel Choir of University College, Durham

Drop, drop, slow tears Kenneth Leighton

The Lamentation Edward Bairstow

Call to Remembrance Richard Farrant

Ubi Caritas Maurice Duruflé

Like as the Hart Herbert Howells

Salvator Mundi Thomas Tallis

Take up thy Cross R.L. Pearsall, arr. Richard Shephard

The Reproaches John Sanders

Never weather-beaten sail Richard Shephard

Crucifixus Antonio Lotti

Geistliches Lied Johannes Brahms

O Brother Man Harold Darke

Jesu, grant me this, I pray Edward Bairstow

Total playing time 60m 37s

God So Loved The World - A Passiontide Sequence

Recorded in York Minster

God So Loved The World - A Passiontide Sequence

God so loved the world lies at the heart of John Stainer’s Victorian Passion meditation, The Crucifixion (1887). The words, chosen by the Revd W.J. Sparrow-Simpson from John’s Gospel, render succinctly and pithily the significance of the Passion story, while Stainer’s simple, homophonic setting allows the text to speak with clarity, direction and force. Although the music is essentially tranquil, there is disturbance here too: ‘whoso believeth in him should not perish’, we are told, but we cannot ignore the dying fall with which Stainer sets the word ‘perish’, straining against the hope contained in the message of eternal life. Such optimism relies, tragically, on the pain and suffering of the Passion.

This pain and suffering is transformed in Phineas Fletcher’s hymn, Drop, drop, slow tears, with music by Kenneth Leighton (1929-1988). Tears fall from the eyes of God as his son descends to the earth as man; these tears become baptismal water bringing the news of Christ’s birth; and they are balm and comfort, washing away the sins of man: ‘In your deep floods/Drown all my faults and fears’. The clarity of Fletcher’s virtually monosyllabic text is matched by the transparency of Kenneth Leighton’s lyrically romantic setting, as the soprano melody flows over the line endings of the poem, suspended above the alto, tenor and bass accompaniment.

Written in 1942, The Lamentation is one of the last choral works to be composed by Edward Bairstow, the organist of York Minster from 1913 until his death in 1946. Recognising the austere potential of Anglican chant, Bairstow set to music selections from ‘The Lamentations of Jeremiah’, chosen by the then Dean of York, Eric Milner-White. At times bitterly angry, at others desolate, and ultimately redemptive, this remarkable text is approached by Bairstow in a strikingly compassionate manner, capturing the constantly changing emotions of the Prophet’s lament with beautifully expressive chants.

Jeremiah mourns for the fall of Jerusalem in 586BC to the Babylonians, led by King Nebuchadnezzar. At first the doleful Prophet laments for the destruction of the great city, ‘She that was great among the nations and princess among the provinces’, until tears of despair overcome him in the second section: ‘For these things I weep: mine eye, mine eye runneth down with water’. The emphasis here is on personal, individual suffering, yet this is evidently a man who only understands self-pity. ‘Jerusalem, Jerusalem, return unto the Lord thy God’, pleads the refrain which separates the three sections of the work; it is only in the final section that we see this process of recognition and renewal beginning: ‘woe unto us for we have sinned’.

Call to Remembrance is similarly penitential and petitionary in character. The words, taken from Psalm 25, accept human failings and appeals for forgiveness. Richard Farrant (c.1525/30-80) was an important figure in Elizabethan church music, the Master of the Choristers at St George’s Chapel, Windsor. He mixed his interest in music with an interest in drama, and the choristers of St George’s frequently performed his plays before the Queen. Despite his prolific output, only three of his liturgical works survive and none of his plays are extant, although their titles, Ajax and Ulysses, and King Xerxes, suggest a preoccupation with tragic themes. Farrant’s interest in drama and liturgical music led to the development of the verse anthem, though the music here is in a more conventional motet form, a sensitive and restrained prayer calling for mercy.

The first of Maurice Duruflé’s four motets on Gregorian themes is a setting of the antiphon for Maundy Thursday, Ubi Caritas. This motet, written in 1960, opens and closes using, unusually, only the lower voices: divided tenors and basses, with an antiphonal alto exposition of the melody, creating a rich, sonorous texture. As with all of Duruflé’s music, including the 1947 Requiem, the plainsong theme is of primary importance; here, the melody evolves organically, unhindered by the regularity of a fixed time signature. This theme, united with its text which speaks of the nature of God and his love, is complemented by Duruflé’s resonant harmonies to produce a motet of unconstrained and extraordinary beauty.

Although it descends from a different tradition, many of the same remarks can be made about Herbert Howells’ setting of words from Psalm 42, Like as the Hart. The melody is driven by a sense of yearning; sung first by the tenors and basses, it is augmented by a flowing soprano descant when this music returns. A single soprano voice floats over the final full choir entry, as Howells’ music reaches further towards the ‘presence of God’. Never heavy, the rich modal harmonies of the organ part are in Howells’ distinctive idiom, sustaining and supporting the melody, and constantly providing material for development. The piece is one of Howells’ In Time of War anthems, a collection of works written over New Year 1941 while he and his family were snowed in to their family home – Howells accomplished the astonishing feat of producing a new work each day.

‘Where is now thy God?’ is the mocking cry that follows the Psalmist. It is through the suffering of the Passion that this ‘living God’ is revealed, and it is to the cross that Thomas Tallis’ motet Salvator Mundi turns. Despite being Catholic during a time of persecution, Tallis enjoyed a successful career, eventually being appointed as Organist of the Chapel Royal in 1570. This motet dates from this high point in his career, printed first in the Cantiones Sacrae, a book of Latin motets dedicated to Queen Elizabeth. The music is solemn and gently imitative throughout, but this never obscures the text; each time a new section of the text is heard, melismatic writing is kept to a minimum, in keeping with Archbishop Cranmer’s earlier advice that ‘the song should not be full of notes, but, as near as may be, a syllable for every note’.

It was R.L. Pearsall’s interest in the music of the English Renaissance, and particularly the secular madrigals of Thomas Morley (1557-1608), that led to an early Victorian interest in music of this period – the musical equivalent, in many ways, of the Gothic Revival. Pearsall (1795-1856) wrote many part-songs, setting the texts used by Morley and his contemporaries; his two eight-part madrigals, Lay a Garland and Great God of Love, are perhaps the most successful examples of these. Pearsall was interested in discovering what contemporary composers could learn from looking at the past, so the Renaissance practice of ‘contrafactum’, setting new words to existing music (often transforming a secular madrigal into a sacred anthem), naturally intrigued him. He experimented by setting the words ‘Tu es Petrus’ to his own Lay a Garland, and Richard Shephard (b.1949) follows this example with Take up thy Cross, setting the words of Charles Everest’s hymn to Great God of Love.

With Everest’s words, Pearsall’s rich harmonies and extended phrase structures involve the listener directly in the drama of the scene: Christ’s words speak with immediacy, ‘Take up thy cross…And humbly follow after me’. Themes of humility and obedience are echoed in Christus factus est: ‘Christ was made for us obedient even unto death, indeed death on the cross’. For this motet, the Austrian composer Anton Bruckner (1824-96) chose a text that reads more like commentary than theatre. Instead, force and drama come directly from the music. Written in 1884, the period of the seventh symphony, the motet is conceived on an orchestral scale; from the simplicity of its sustained piano opening, invoking the mystery of the incarnation, through the exhilaratingly triumphant climax of ‘quod est super nomen’, to its whispered conclusion, the music demands that the human voice is stretched to its limits.

The demands made by John Sanders’ setting of The Reproaches are arguably even greater: this is not the human voice, but the divine – the suffering Christ reprimanding man from the cross for the injustices of the crucifixion: ‘O my people, What have I done to you? How have I offended you?’ This poem-like chant would originally have been sung by a Priest to a plainsong melody during the Veneration of the Cross, and the verse sections of Sanders’ twentieth-century setting clearly recognise this heritage. There is a sense of balance in these chants, which render Christ’s words with painful simplicity, as each reproach grounds the cruelty of the Passion in the context of God’s good deeds to his people: ‘I led you from slavery to freedom, but you led your Saviour to the cross’.

Despite the striking nature of these verse statements, it is in the two refrains, ‘O my people’ and ‘Holy is God’, with their block dissonances and thick textures, that the real power of Sanders’ setting is felt. The insistent repetition of material relentlessly keeps the focus of the music on the ingratitude and sin of the people of God. The only response that can be made is found in the penitential Trisagion, ‘Holy is God’, petitioning for mercy. But the inadequacies of this are difficult to ignore; unable to justify what has happened, the congregation is ultimately speechless as Christ’s demand ‘Answer me!’ dies away into plangent silence.

Expressing the divine in human terms is central to Thomas Campion’s lyric Never weather-beaten sail, which looks forward from the exhausting, world-weariness of life towards the ‘Ever-blooming…jo

The Nicene Creed sums up the facts of the crucifixion with almost brutal clarity: ‘He was crucified also for us, under Pontius Pilate: he suffered, and was buried’. Although his output was prolific, Antonio Lotti (c.1667-1740), who lived and worked in Venice for most of his life, is remembered now mainly for this Crucifixus, originally part of a full setting of the Creed. The opening, excruciating suspensions setting the single word ‘Crucifixus’ are unforgettable, building from this single voice entry up to the full choir climax on ‘passus’, articulating with incredible emotional intensity the pain of the Passion, before fading away to the simple statement ‘et sepultus est’.

Considering its natural ease and beauty, it comes as a surprise to note that Johannes Brahms’ Geistliches Lied (‘Sacred Song’) was originally composed in 1856 as little more than a musical exercise in counterpoint. Formally, the music is a strict double-canon at the ninth; the tenors imitate the soprano line, and the basses the alto – and to add to this complexity there is also imitation within the organ accompaniment. Brahms’ real achievement here is that this learning never obstructs the music; throughout, there is a pervading sense of lyrical calm, entirely in keeping with Paul Flemming’s poem, before finally blossoming into a glorious ‘Amen’.

The words of John Greenleaf Whittier, the American poet most famous for writing the hymn ‘Dear Lord and Father of mankind’, clearly respond vividly to musical setting, and it is obvious that Harold Darke recognised this when composing the anthem O Brother Man in 1959. This anthem is dedicated to the composer William H. Harris, and although the scale is different, it bears comparison with Harris’ own miniature, ‘Holy is the true light’. Darke’s anthem opens expansively, almost declamatory in tone; with delicate word-painting, Darke picks up on the word ‘Follow’ which opens the second stanza, leading into a gentle fugato passage. The singing of beautiful hymns, psalms and prayers are contrasted with the bitter violence of ‘the stormy clangour/Of war’s wild music’, which is ultimately supplanted by the ‘tree of peace’.

Jesu, grant me this, I pray opens with a statement of Orlando Gibbons’ hymn tune ‘Song 13’. Gibbons (1583-1625) was one of the most influential church musicians of his age, and it is fitting that Bairstow, with his growing interests in music of this period, should base this astonishingly beautiful motet on one of Gibbons’ most affecting hymns. Bairstow treats the melody in a fauxbourdon manner; the melody moves around the parts but is always present. Despite the simplicity of the opening, or the beauty of the descant in the second verse, or the anger and fury of third, it is perhaps the way in which the music ends that is most memorable; the melody, grounded low in the bass register, provides the foundation for the other voices as the poet’s thoughts turn to the inevitable approach of death: ‘Dying, let me still abide/In Thy heart and wounded side. Amen’.

Simon Jackson

Peterborough, 2005

The Chapel Choir of University College, Durham

University College Chapel Choir is made up of eighteen students, the vast majority of whom are members of the college, though students from other colleges are welcome to join. Also, much of the time (though not on this disc), two of the university’s professors take the total number of singers to twenty. During term time the choir sings Evensong every Thursday before formal dinner, as well as at the majority of Sunday morning Eucharists.

Over the past year the choir has taken on many varied engagements. Ranging from performances of Haydn’s Nelson Mass in both Newcastle and York, to providing live music for a production of Peter Schaffer’s play Amadeus in Durham Castle. However, it was the choir’s performance of Michael Tippett’s ‘Five Negro Spirituals’ from A Child of our Time at the Edinburgh Fringe in the summer of 2004 that saw them beat off international orchestras and choirs to win the ‘Schott Musik International Youth Choir Award’.

David Jackson

David Jackson was born in York in 1983. From 1992 to 1996 he was a Chorister at York Minster, becoming Head Chorister and winning the National Choristers’ Composition Competition. He subsequently attended St Peter’s School, York where he was a music scholar. After leaving St Peter’s School, he spent a gap year working at Wells Cathedral Junior School in Somerset. During this time at Wells he accompanied the school choir on a live broadcast from Liverpool Cathedral for Classic FM, and joined them on tour to the Edinburgh Fringe.

David graduated from the University of Durham in June 2005 after reading music and specialising in performance. He joined the University as a member of University College in 2002, and in his first year was the Assistant Organ Scholar under the direction of Christopher Totney - performing on the choir’s first release with Lammas, Cantate Domino. For the past two years David has been the Senior Organ Scholar, directing the choir at all concerts and services. He took the choir on tour to the Edinburgh Fringe, where they won the ‘Schott Musik International Youth Choir Award’, and has directed them in services, concerts and even theatre performances. David has been playing the organ since he was fifteen, and has been taught by Gordon Stewart and most recently, Keith Wright in Durham.

In York, David is a frequent soloist, and conductor of the York Young Soloists, most recently directing a performance of Finzi’s Eclogue in January 2005, and he continues to sing at York Minster as a member of the St William’s Singers.

The recording of this CD marks the end of David’s very enjoyable three year association with University College Chapel Choir, and the University of Durham. David now moves to Glasgow, to study for a postgraduate degree from the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama.

Oliver Bond

Oliver Bond was born in 1983 and began to learn the organ at the age of 11. Upon coming to Durham to read Music and German, he began studying organ under Keith Wright at Durham Cathedral. Before commencing his organ scholarship at University College Chapel, he co-founded and directed the St Cuthbert's Choir in his college. He also spent a year teaching at the Peter-Altmeier-Musikgymnasium in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. Whilst there, he spent much of his time accompanying and singing with the school's successful mixed choir, Art of the Voice, in various concerts and competitions and continued his organ studies with Professor Markus Eichenlaub at Limburg Cathedral.

Oliver now lives in London and is currently studying for his ARCO diploma.

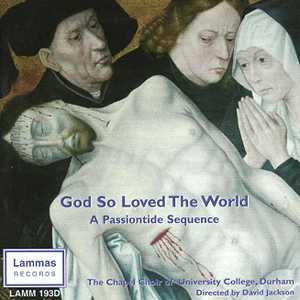

Cover Picture

The Lamentation: The Dead Christ supported by John the Baptist, Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus with the Virgin Mary and Mary Magdalen. After Hugo van der Goes (c.1440-1482)

Hugo van der Goes was active in painting public pageants and complex altarpieces. The Lamentation (University College, Durham) is one of seventy versions, painted after a lost original, of which the finest may be found in Amsterdam, Naples and Ghent. His most famous work, in which he rivalled the more successful Rogier van der Weyden (c. 1400-1464) is the Portinari Altarpiece in the Uffuzi collection in Florence. It is believed that the artist's consciousness of his rival's superiority led to his mental decline and his retreat to a monastery in Bruges.

The dead Christ, surrounded by his closest mourners, is turned towards the viewer to display his wounds and to inspire meditation. His mother appears calm, perhaps reflecting her confidence in the Resurrection. The drapery is painted in strong colours with elaborate costume detail and the diagonally flowing trickles of blood, carefully considered, remind us that the wounds were inflicted whilst vertical on the cross.

York Minster Development Campaign

This CD was recorded in York Minster, by kind permission of the Dean and Chapter. The recording coincided with the launch of a development campaign, designed to do three things: first, to conserve, repair and restore the east front and east window; second, to establish an endowment fund for the Minster's music and thirdly to ensure the future of the Minster's educational programme through the Centre for School Visits and the Minster Library.

The East Front Project is the largest and most important conservation project in Europe at the present time (2005). The 15th century stonework has come to the end of its life, and the replacing of the delicate tracery in the window necessitates the complete removal of all of the priceless mediaeval stained glass. The Great East Window - described as the Sistine Chapel of stained glass - is about the size of a tennis court.

The Dean and Chapter hope that many people will come to visit York Minster as the work progresses. More information can be found and donations made at the York Minster website.

Produced by Stephen Shipley

Recorded and edited by Lance Andrews

Recording assistant: Andrew Bell

Cover photograph by Andrew David Teasdale of The Lamentation. After Hugo van der Goes (c.1440-1482)